Parents and teachers want to know: What is Montessori? More importantly they want to know the Montessori Basics: how they can use the ideas of Montessori education to enrich their home environment and help their child grow.

There are many misconceptions about Montessori education. Some think it’s really loosey-goosey (not true: folks are surprised at how structured it is!), that it’s just for wealthy kids (again not true: there are public Montessori schools all over the country, including the one that I lead), and that it’s about buying wooden toys and having a (snotty) minimalist style. This last one… well it depends on the practitioner.

Montessori schools are all different, but most adhere to some general guidelines around Montessori education: multi-age classrooms, an uninterrupted 2-3 hour work block where students pick work of their choice, and an individualized approach to teaching.

But if you’re interested in learning Montessori basics for implementing some of the most important principles of Montessori education in your home, it really boils down to a set of beliefs about WHAT education should be and HOW it should be done.

In another post I cover bringing Montessori principles into your home but here, as a Montessori school principal (and mom!) I outline my favorite Montessori basics that will help you understand the core teachings.

The focus is the point

Montessori educators are unique because their primary goal is to follow the child and watch them as they learn. In a Montessori classroom, children interact with an environment that provides materials and lessons for them, leaving teachers (or guides) to hover and watch, intervening only when necessary.

From 25 years in education, I can say that the most important basic function of early education program needs to be the development of focus. It is the foundation of everything else!

The capacity to learn is completely dependent on the ability of the child to sustain focus.

If your child doesn’t develop the ability to focus on a task completely, giving it all of their attention and interest, they will struggle to engage later when the tasks are more complex. If a child learns to focus, is given practice at focusing on an object or a task, that child is being given a huge gift of capacity.

The capacity to learn is completely dependent on the ability of the child to sustain focus.

So what to do? Don’t interrupt. It’s almost that simple.

When your child is playing with the door knob over and over again, seeing how it spins back and forth, opening and closing the door over and over and (possibly) annoying you and the rest of your family: ignore it.

What your child is doing is learning. And focusing hard. This is exactly what they should be doing, and this ability to focus for a long time on an interesting task is going to set them up for school success.

This means that if your child is creating a masterpiece at the kitchen table, try to leave them be instead of chatting with them about it. If they aren’t interested in talking to you, let them work quietly.

It also means that you might see them make mistakes or get something wrong. I say, leave it to their teachers and let them keep focusing. Anything you can do to let them work in an uninterrupted way is beneficial.

Tips for helping your child develop focus

Let their interest guide them

This is one of the most important Montessori basics. Rather than directly teaching young children what WE think is important, our children’s interests should be followed.

As a school principal I believe that children in K-8 education should be directly taught skills and content. However, self-directed work is one of the best ways for our children to develop their interests and also develop their skills. At our school, we blend the two. At home, I direct very little for my daughter.

This means that we offer materials and allow children to follow their interests. Children learn much more naturally when they are interested in a topic or a task. Then, the “work” of education becomes following their own interests and seeking to understand the world. The Montessori education is about guiding children to understand their world, not about filling them up with skills and content.

One of the Montessori basics that I live by is that young children do not need constant exposure to letters and numbers. In our house, The Girl had very little exposure on purpose to the basic early childhood toys with letter repetition and battery-operated counting. Not only do I find those annoying, but they’re not necessary.

Each child learns according to their own timetable, and the natural progression of skills happens differently for each child. Especially between ages 0-5, there is a HUGE variation between what kids can do at different ages. By age 7, it has evened out considerably. So don’t fret if your three year old can’t count to 100 like your neighbor’s kid does. You kid is probably more interested in lining up dinosaurs by height, and has the capacity to remember all their names. To each his own, at this age.

These two three year old kids: one who knows dinosaur names and the other who counts to 100--both of them are doing great.

These two kids: one who knows dinosaur names and the other who counts to 100-- both of them are doing great. Education is not about knowing a particular order of things. It’s about following your interests and gaining skills along the way. The skills of ordering, spacial awareness, and object discrimination are JUST as important at 3 as counting skills. I'd frankly rather have my child spend their time lining up dinosaurs and exploring their qualities than memorizing numbers. (Which, let's be honest, is all counting to 100 is at the age of 3.)

Let your child pick their work and trust that they are deepening their skills and knowledge of the world as they’re doing it.

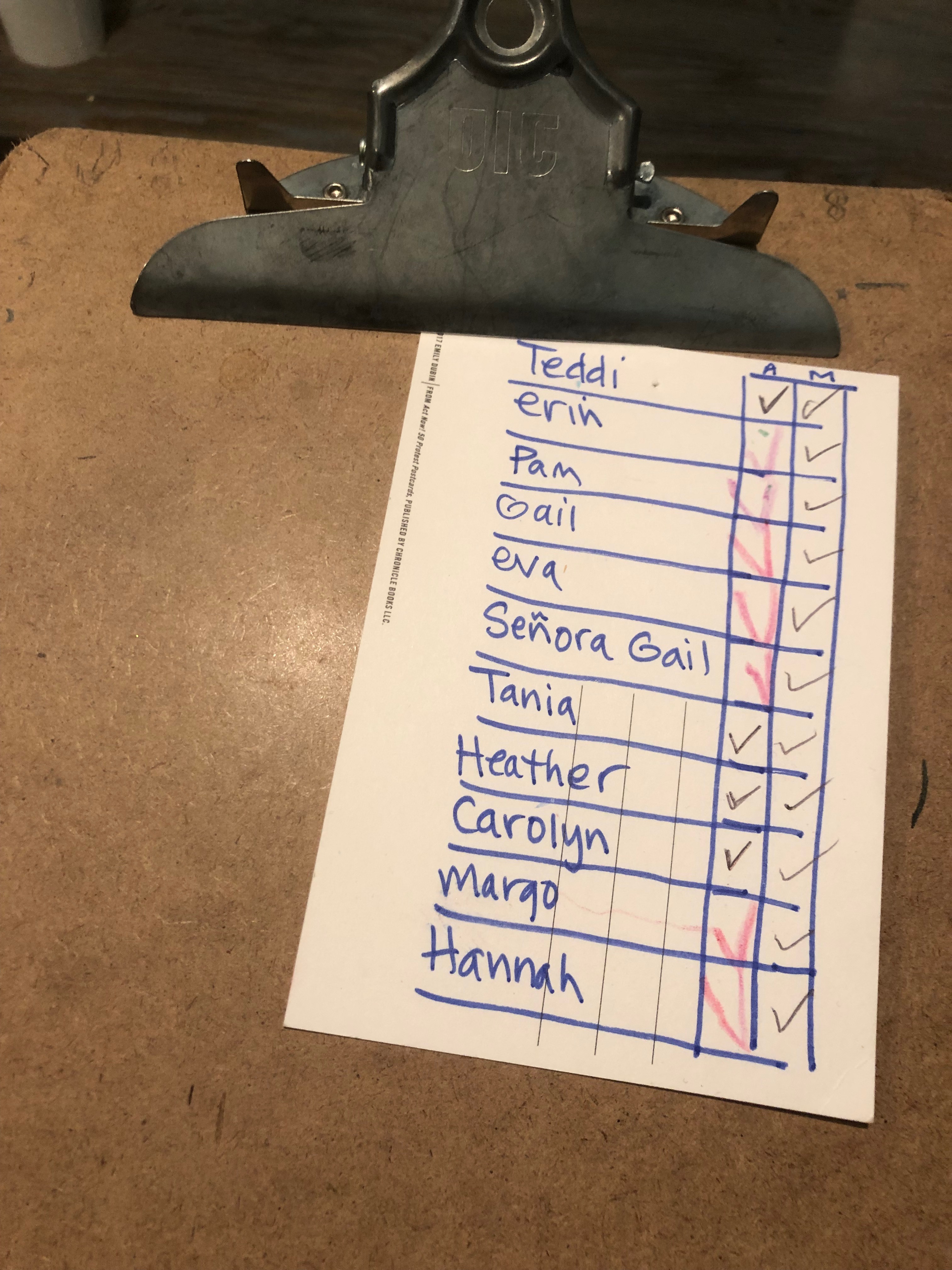

My daughter loves writing. She particularly loves writing her name, her teacher’s names, my name, her friend’s names. She loves making long lists of her friends and writing thank you letters with elaborate signatures. At 4 she was interested in cursive writing, something that was not on the curriculum list but she picked up and started to try to learn.

When it came time to give her teachers presents at the end of the school year, my daughter (of course) wanted to write a letter to each. I did too, so we made a grid and each checked off each teacher as the letters were written.

Does it matter that we didn’t practice counting at all at home this month? Nope. She is thriving and deepening her understanding of language and writing. Following her mind and allowing for her interests to flourish is the best approach to supporting her education.

So you don’t have to buy a pre-school readiness book and start working on worksheets. Unless there’s a reason (like you’re testing into Kindergarten and she needs to demonstrate certain skills) then don’t obsess over what she knows.

Tips for following their interest

Learning is its own reward

Montessori doesn’t use extrinsic rewards because one of the key Montessori basics is that learning itself is a reward. Tying any kind of reward to educational activities (like earning money for getting certain grades or earning ice cream for finishing the worksheets you assigned) sets up learning as something that needs external reward. That affects your child’s ability to see the point of learning itself, which is learning.

I am not opposed to rewards. Society has all kinds of rewards and we choose to try for them or not depending on our motivation. (Obviously, the “reward” of driving around for free is not something I’m interested in because I get SO many red light speeding tickets). I also think that older children who have not developed the internal drive toward learning may need an extra kick in the butt to get motivated.

“Our aim is not merely to make the child understand, and still less to force him to memorize, but so to touch his imagination as to enthuse him to his innermost core.”

-Maria Montessori

But for young children, they are already motivated to figure the world out. They arrive ready and programmed for it. As long as possible, put off introducing rewards for learning so your child’s development and interest in the world can grow naturally.

Also make sure that your praise for learning is restrained. When you figured out that tricky google email glitch, you did it because you were motivated to get your email inbox problem solved. You weren’t doing it for your husband’s praise or your daughter’s admiration.

When we over-praise or turn learning into a thing that kids do for us, we take away some of the internal drive to solve problems. Show your child you saw how hard he worked, or notice that he must be so excited to have solved that problem.

Tips for helping them develop internal motivation

These Montessori basics will help you think about how to introduce your child to Montessori principles in the home. Without working too hard, you can become a Montessori family by prioritizing the time your child spends working, not interrupting them, and following their interests. Good luck bringing these Montessori principles into your home!

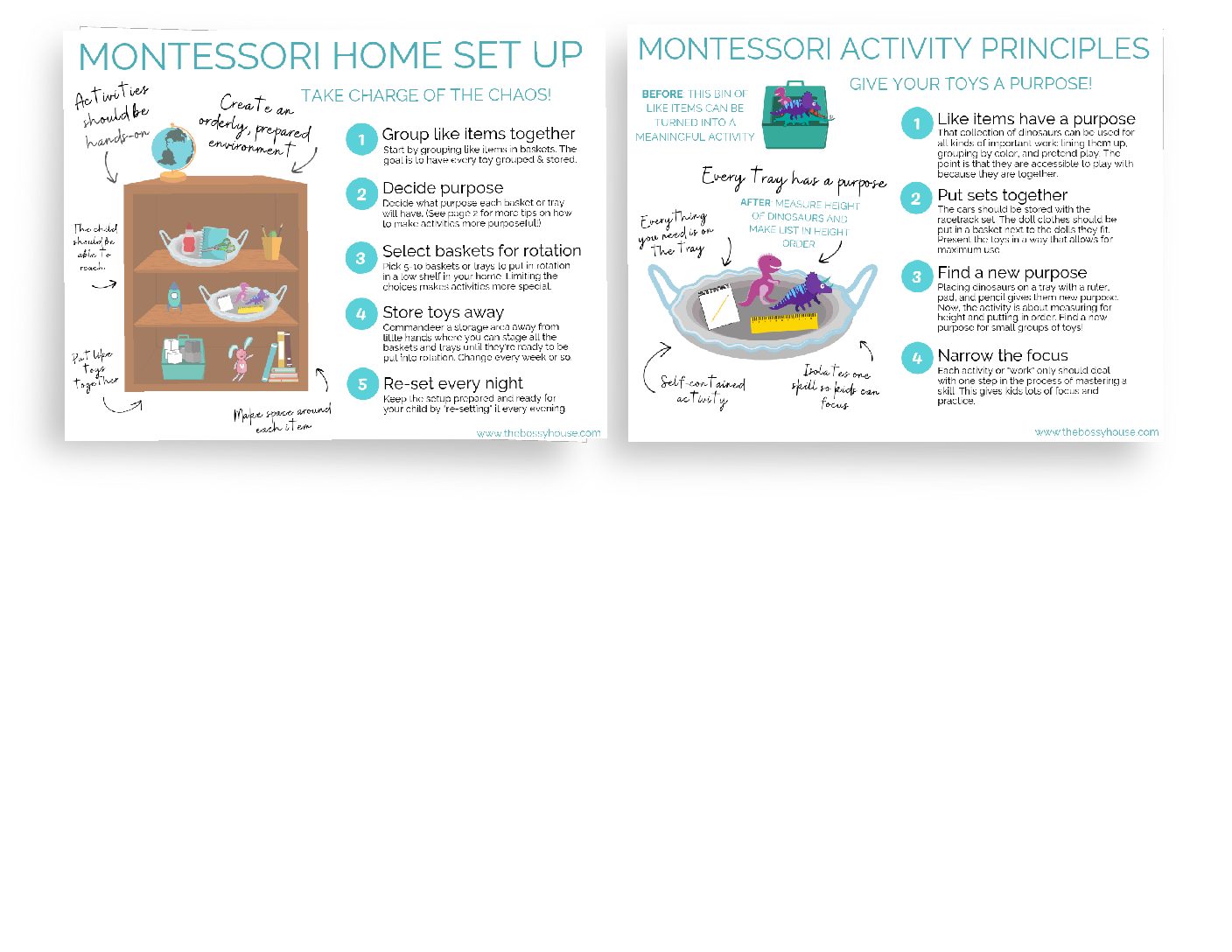

Get this two-page Montessori Set Up Guide to get started setting up your home with Montessori principles!

Often the most simple advice is the correct advice. As you said, “Do not interrupt.” Let the process and questions unfold naturally.

I love the Montessori way of teaching kids. It’s a very supportive, natural and effective approach to guide children in the learning process. I remember years ago my oldest getting obsessed with the book Madeline and learning all things French, it was so much fun and we learned so much!

Following their mind can be so fun!

What a wonderful article about Montessori! I work in Early Childhood Education; I have read a lot about Montessori and use it in my practice. It is a really incredible way for children to learn.

Thank you! So wonderful you use it at your school.

What a great way to help find your kids’ motivation and interest. I will definitely be using some of these concept during the summer to help my kids become more well rounded while still learning.

Summer is a great time to start!